Samuel Crompton was born on December 3rd, 1753 at 10, Firwood Fold. Samuel's father, George, had married Elizabeth Holt from Turton and besides Samuel, they had two younger daughters.

Their ancestors had owned this farm and tenanted several acres of land. Samuel’s Grandfather (also George) on the birth certificate of one of his children was called a “yeoman” but later on the birth certificate of his youngest child he was a “weaver”. This attempt to combine manufacture with farming seems to have been less than successful as he mortgaged the farm to the land owners the Starkies of Huntroyde familiar names of Tonge Moor and Top o’ th’ Brow. Shortly before Samuel was born he sold the farm to Mr Starkie and after remaining in the farm for a short while as a tenant and spending some time in Lower Wood, Tonge the family took up residence in Hall i’ th’ Wood which was partitioned to be occupied by a number of families. This move was probably because it gave George a source of income as caretaker.

George died at the early age of 37 (32?), but Elizabeth continued to live at Hall i’ th’ Wood and took a lease on the building with five acres of land in 1764. Though hardly well off she managed to provide Samuel with an education at the school of Mr Lever where he attended classes under William Barlow. The school was in Church Street just 500 yards as the crow flies from the barber's shop of Richard Arkwright in Churchgate. Perhaps the inventor of the spinning mule had his hair cut by the supposed inventor of the Water Frame.

According to Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Crompton ruled her family with a rod of iron and Samuel's childhood was miserable. "She cuffed, thrashed and maybe even swore at him with tremendous zeal and energy," he wrote. "...she set her children to earn their bread betimes, and tied them down to the loom as soon as their little legs were long enough to work the treadles."

Dickens wrote a three volume “A child’s history of England” but this quote may have come from somewhere else.

At some point it is recorded that the girls worked at spinning linen and cotton yarns while Elizabeth and Samuel were occupied with weaving.

George died at the early age of 37 (32?), but Elizabeth continued to live at Hall i’ th’ Wood and took a lease on the building with five acres of land in 1764. Though hardly well off she managed to provide Samuel with an education at the school of Mr Lever where he attended classes under William Barlow. The school was in Church Street just 500 yards as the crow flies from the barber's shop of Richard Arkwright in Churchgate. Perhaps the inventor of the spinning mule had his hair cut by the supposed inventor of the Water Frame.

Hall i' th' Wood (C)WDC Oct 2006

Later, still at Hall i’ th’ Wood just three years after the spinning jenny became available to the public (around 1769 Samuel then being of age 15 or 16) Samuel was using this machine for spinning the yarn needed for the family’s looms.

He tried different ways of running the jenny and tried to make improvements to it so that he could spin stronger thread for use as warp but was largely unsuccessful. By the age of 19, convinced that he make a better spinning machine he used an empty room at Hall i’ th’ Wood and started his attempts to design such a machine. Over the next five years all his spare time and all the money earned, including that from a side income playing his (home-made?) violin at a Bolton theatre (apparently he was a very accomplished musician) for a few pence a night, went on building his spinning machine.

Above the porch at Hall i’ th’ Wood is a small study that Crompton called the “conjuring room” where he spent many hours trying to solve the problems.

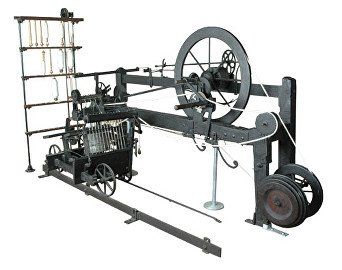

The Hall i' th' Wood wheel (mule) begins work

In 1779, now aged 26, Samuel Crompton finally had a working device which produced yarn strong enough to be used as a warp thread, but he could also produce very fine, strong yarns suitable for making muslin – and it is thought that his device was first known as the Hall i’ th’ Wood wheel and the muslin wheel. It was later referred to as the Mule because it combined drafting rollers like the water frame with a moving spindle carriage like the spinning jenny (though in truth the similarities were superficial, Crompton’s principal of operation being rather different from that of the Jenny). Crompton did not refer to it as a mule in the first place because he claimed that he was unaware of the rollers in the water frame and had designed these himself during his five years work.

Some historians say that it is unlikely that he created such a similar design independently and point to the fact that Thomas Highs - the originator of both the spinning jenny and the water frame was living in Bolton around that time and that Highs and Crompton were both members of the Swedenborgian sect.

There are conflicting accounts about the origins of Swedenborgism in the UK and Crompton's connection with the "New Church" in Bolton.

The Mule was working by 1779.

The official inauguration of the Swedenborgian Church in the UK is 7th May 1787.However Swedenborg paid many visits to England prior to 1787 and it seems that in various parts of the country, around Manchester especially people were meeting together to discuss his theories. In Bolton it seems o be without doubt that members of a Swedenborgian society were worshipping is a building in Bury Street as early as 1781.It seems that Crompton became a member of this society, the so-called New Jerusalem Church, around the year 1791 (gracesguide.co.uk/Samuel_Crompton) and finding himself reasonably well-off by 1803 was able to lend £100 for the erection of a new church building in Bury Street. Samuel Crompton’s name has been found among a list of subscribers as a member of the New Jerusalem Church 1791.

These dates still indicate that Crompton could not have discussed spinning machines with Highs while both were members of the Bolton New Jerusalem Church.

If the two men were members of the same Unitarian style sect at the same time one would guess that they would almost certainly have discussed the other topic that they had in common, spinning machines. If these discussions took place it might be that the men met at the Bank Street Unitarian Church before the formation of the Bury Street society. The discussions would have had to have taken place before 1779. It might be best to assume that they did not in fact take place.

Bolton's Swedenborg congregation moved into this "New Jerusalem Church" on Higher Bridge Street in 1844.

It has been a carpet warehouse for many years.

By this time Crompton had moved out of Hall i’ th’ Wood and was living in King Street just off Deansgate, in Bolton.

A booklet on Hall i’ th’ Wood, undated but published by Tillotson and Company probably around 1960 describes the organ that is displayed there as “the organ played, and probably built by Crompton while he was choir master at the Bury Street Swedenborgian chapel”. Another source is more specific saying – He built an organ at King Street and while he was the Bury Street choir master he practiced the choir there, with the organ until it was removed , then with a piano. This ceased in 1823 when there appeared to be some difference between Crompton and the minister. He had also served as the Church's Treasurer.

Some years later this instrument passed into the possession of Mr William Tickle who either sold it to - or more likely had bought it for - the Bury Street Church where it was in use until the congregation moved to the Higher Bridge Street Church. It was then sold to Mr Walmesley of Spaw Lane (now Spa Road). This instrument has been in the Hall i' th' Wood museum for many years.

The question of Crompton's discussions with Highs led us to a consideration of his association with the Swedenborgians An we must now go back a few years and return to Hall i' th' Wood.

Samuel soon found that more money was to be made producing yarn to sell for other people to use than to use it for his own weaving. He produced cotton of 40 count of better quality that anyone else. (Count is a measure of thread weight and thickness. It is the number (count) of hanks (840 yd or 770 m) of thread that weigh 1 pound.) He earned 70p a pound for 40s – that is a length of 40x840=33,600yards=19miles or so. As his skill increased, he produced 60s that sold at £1.25 a pound (29miles). Soon, he was producing 80s (38miles) for £2 a pound. We do not know how long it took to produce one pound of thread but wages at that time were less that 10/- a week. It is stated that he was earning four or five times more with his spinning than any weaver could earn.

For a time when machine-breaking riots broke out in the area (Richard Arkwright’s factory in Chorley and Mr Kay’s carding mill at the Folds in Bolton) Samuel dismantled his machine and hid the parts in the attic at Hall i’ th’ Wood.

Part of one of Crompton's mules can be seen in Hall i' th' Wood at the present time.

So Samuel became moderately well off and on 16th February 1780 he married Mary Pimlott in Bolton Parish Church. There is a street on the Hall i’ th’ Wood estate named after her. (A historian trying to research Mary’s origins, (she hailed from Turton but was originally from Warrington) could not find her and suggested that her name had actually been Mary Pimbley, Pimlott being an copying error at some stage.)

Apparently he also bought himself a watch (pictured right) costing five guineas (ten weeks wages for most people, perhaps a sign that he was less than astute as a businessman.

As Crompton’s finer cotton began to appear local competitors were increasingly curious as to how it was being produced. Stories abound of spies climbing ladders to peek into the first floor window at the mule. Samuel and his wife even resorted to spinning behind screens to protect his secret. It was clear that Samuel’s invention had great potential beyond his small scale spinning at the Hall.

MAKING THE MULE PUBLIC

Could Samuel secure a patent for his machine then he could reveal it to the world?

Unfortunately Richard Arkwright had already patented the water frame, and protected copying of the invention vigorously. As a result Samuel was persuaded not to try to apply for a patent himself. Samuel consulted John Pilkington, a respected local merchant. Pilkington was a member of the Manchester Council of Manufacturers, a group that was opposed to patents and the monopolies that these created. He had witnessed already “the strangling of the developing textile industry by the patent rights held by Arkwright for roller drawing in spinning machines”.

Perhaps he was not the best person to ask about patents!!

He offered Samuel the opportunity to display his machine to other Council members at the Exchange in Manchester. A fee of £200 raised by subscription was customarily awarded to any inventor displaying models of their machines on the Exchange floor. Unfortunately few were impressed by Crompton’s humble looking machine and many refused to pay. They were also mindful of the patent issue and even if they wanted to install a mule they would not do so until Arkwright’s patent expired in 1785. Samuel only earned £60 from the showing.

Instead of investing this money in building more or better mules, Samuel took his wife and new son to a new home at the Oldhams in Sharples. They took up residence there in 1782, where he farmed and wove in the traditional manner of the cottage weaver. He installed two mules in the farmhouse but found it difficult to keep staff working for him. Every time he trained a new mule spinner they were lured by higher paid work and gave away the secrets of the mule’s construction to their new employers.

Sadly for Samuel Crompton, his having shown the mule at the Manchester Exchange and many people realising that this machine was the means by which Crompton produced such superior yarns, copies were being made, powered mules built in cast iron instead of wood had more and more spindles and factories were equipped with mules totally outside Crompton’s control – and in most cases knowledge.

Unable to compete with the new factories, which had been started with the water frame but more and more equipped with copies of the Mule, Samuel’s fortunes continued to slide. He also refused offers of employment and partnership by Sir Robert Peel of Bury in 1780 and a similar offer from Mr. W. McAlpine in 1785. Samuel was committed to being self-employed though the steady pace of industrialisation was quickly making his ideal, working as an independent cottage spinner and weaver, irrelevant and unviable.

A notice in Hall i’ th’ Wood suggests that it had been Crompton’s intention that the Mule would be for the benefit of the cottage worker but the factory system was unstoppable.

If you can't beat them, join them

King Street, off Deansgate, Bolton

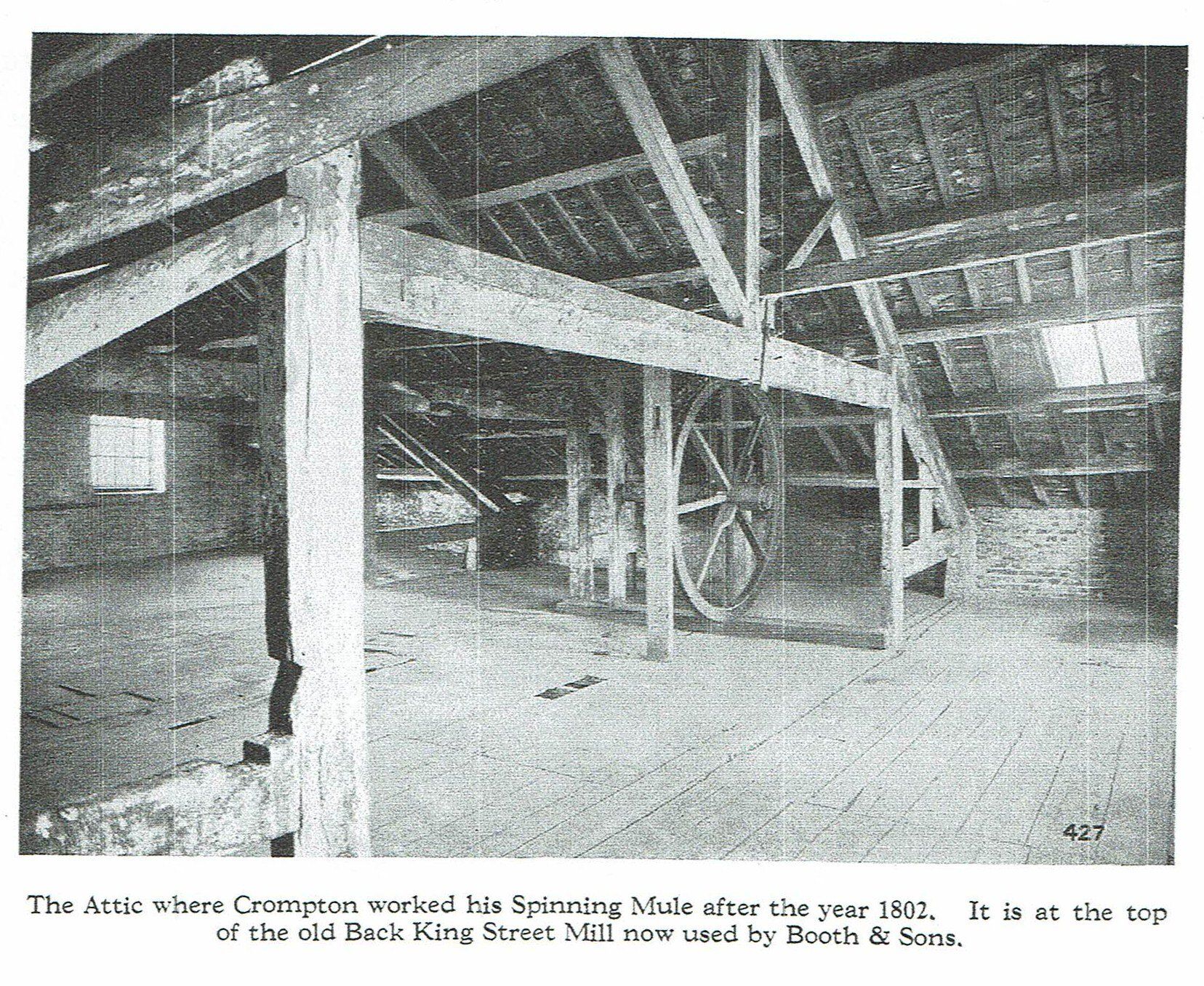

The attic of the Back King Street, mill where Crompton set up his mules in 1802 (possibly 1800)

The family moved into King Street in Bolton in 1790. Rate books show him at number 15 in 1800.

Crompton extended his spinning operations and became a tenant of the upper storey of a factory (built 1797) in Back King Street (between there and St Edmund’s Street) and installing there two mules of 360 and 220 spindles.

(The mill was taken over by John Booth and Sons, steel works, in 1894. Gordon Readyhough (Bolton Town Centre – A Modern History) says “For many years a board attached to the roof announced that ‘In this ancient Mill Samuel Crompton first worked his spinning mule 1800’ and Crompton’s tenancy is apparently mentioned in the mill deeds.” Note the ambiguity. Crompton first produced yarn from the Mule in 1780 so the “board” does not imply 1800 as when Crompton “first worked” the Mule, but that he worked it in that mill from 1800.)

The Back King Street mill

Crompton may have made only £60 from his invention but others copied it and prospered from its use, not only cotton spinners but also machine builders such as Isaac Dobson, founder of the Bolton firm Dobson and Barlow. In 1802 a group of manufacturers who had profited on the back of Crompton’s invention decided to raise a further subscription for him. Perhaps their consciences had got the better of them. Even this gesture appeared half hearted as they only managed to raise £444 of the £872 they had promised. Not one payment came from Bolton manufacturers.

Even so, Crompton rallied and invested this money in his workshop to increase capacity and to start selling high quality cloth. The mule in Bolton Museum’s collection comes from this workshop.

This was the time when the factory system for cotton spinning was taking off. In 1824 there were 24 factories in Bolton; in 1835 there were 42; in 1839 there were 69 with 9918 workers. But weaving continued to be a cottage industry.

CROMPTON BEGINS HIS FIGHT FOR RECOGNITION

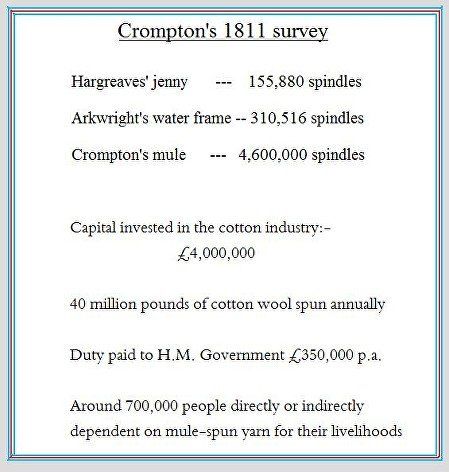

In 1809 Parliament awarded Edmund Cartwright the inventor of the power loom a £10,000 reward for his invention. Crompton decided it was about time that his efforts were similarly rewarded. In 1811 he toured the 650 cotton mills working within the 60 mile radius of Bolton gathering evidence of how widely the spinning mule had been adopted. He would use this to petition parliament for compensation.

He found that:

•Of the spindles in use 155,880 were on Hargreave’s jenny, 310,516 were on Arkwright’s water-frame, and 4,600,000 were on Crompton’s mule

•The capital invested in the cotton industry was worth nearly four million pounds

•40 million pounds of cotton wool was spun annually

•Duty paid to H.M. Government was £350,000 per annum

•Around 80% of the cotton goods bleached in Lancashire were woven on Mule-spun cotton

•He concluded that around 700,000 people were directly or indirectly dependent on mule-spun yarn for their livelihood.

Many letters exist written by and to Samuel Crompton between 1810 and 1812 concerning this survey and his appeal to Parliament. He was supported by Sir Robert Peel, John Pilkington (mentioned earlier and with a street named after him off Derby Street), James Watt (of steam engine fame), Thomas Ainsworth and Joshua Ridg(e)way (with crofts in the centre of Bolton and remembered by Ridgway gate off Deansgate.

In support, James Watt testified that two thirds of all the steam engines installed in spinning mills by his company were for running mules.

The spinning mule, Crompton concluded, had become the mainstay of cotton spinning in Britain.

Samuel took his evidence to parliament in 1812 expecting £50,000 compensation. Again timing was against him, the national economy was funding the Napoleonic wars. Samuel’s supporters convinced him to ask for £10,000 to £20,000. Another stroke of bad luck occurred when Spencer Perceval the prime Minister was assassinated. (worse luck for Spencer Percival, perhaps.) Legend has it that at the time he was on his way to recommend that Crompton be granted the sum he requested. This is disputed though. At the time of his death it is likely that Perceval was hurrying to a committee dealing with an unrelated matter. In the end the new chair of the committee overseeing Samuel’s claim only awarded him £5,000. But this is more or less equivalent to £1million today.

NEW WEALTH - NEW BUSINESS - SAME BAD LUCK

He moved to Darwen and built a house at Low Hill, Bury Fold Lane, Darwen. It was a grand enough house but our picture includes east and west wings added later by the Shorrock family who occupied it for 100 years after Crompton left.

In Darwen in 1812 he started a new bleaching business in premises known as Hilton's Higher Works in Spring Vale, having as partners his sons George and James. This seemed to go well enough for a while but coal pits were sunk nearby and these had the effect of diverting the spring water away from the bleaching works. More bad luck. In attempts to remedy this he was involved in a costly lawsuit. It has been reported that his sons were disorganised and lazy so overall the business did not thrive though it may be more correct that at least one son worked hard while two others joined the army then returned home and tried to have their say in the running of the company after some years of taking no interest, leading to family disagreements. However Crompton gave it up after six years. Eldest son George started a separate bleaching business at Hoddlesden which also failed.

In this period he also ran a cotton trading business taken over with his then partner Richard Wylde of Ridgway Gate, Bolton from the previous owner who was in financial difficulties. You can’t say he didn’t try! This was quite successful until the warehouse in Delph where the business was based was washed away in a flood. (This is not Delph near Oldham but a small hamlet north of Bolton where the Delph Reservoir is now, Longsight Road, Egerton.)

BACK TO KING STREET, BOLTON – POOR AGAIN – THE BLACKHORSE CLUB

Now in debt, at some point he moved back into King Street in Bolton where he worked as a weaver, but his fine pieces were too expensive for most people to buy and his designs were stolen by people who made inferior copies but at a cheaper price.

King Street is almost opposite Blackhorse Street (called Thweate Street at the time) on which, very close to Deansgate. was the Blackhorse Hotel from which the street later took its name. Now the area between Blackhorse Street and Moor Lane, and from Deansgate up to New Street (behind our Ashburner Street market) in other words the whole of the area where the bus station (until its moving in 2017) and the market now are, was crammed full of iron works and brass works. Even though it was demolished in the early 20th Century, even when I was young people still referred to the Bessemer Furnace there. This is where the locomotives for the Bolton and Leigh railway were made (although that started about fifteen years later than our present interest, a little after 1828). But at this time, among other things like domestic cast-iron fire grates these companies would have been making water frames and spinning mules for use throughout Lancashire and further afield.

Isaac Dobson (founder of what was later Dobson and Barlow) lodged at the pub shortly after he arrived in Bolton in 1789. Very soon he was joined by other ironworks and engineering bosses, Benjamin Dobson (presumably his brother), Peter Rothwell (owner of Union Foundry whose name is commemorated off Derby Street (he later made locomotives)) and Benjamin Hick (co-founder of Hick-Hargreaves) These men formed ‘the Black Horse Club,’ an informal business club.

So can you imagine these clearly well off, important people meeting in that pub – mostly as a social get-together but often discussing business, iron forging, the next development of the cotton machinery they were manufacturing – and in a far corner, with a hat and jacket that had seen better days, an older man trying to make one pint last all night? That man was Samuel Crompton. However that picture was not quite true because Samuel was himself part of the Black Horse Club though he was described as “famed at the Black Horse for sitting with his one glass of ale and seldom speaking, except when directly addressed, and then always briefly and to the point.”

In 1823, the Black Horse Club, under the name “The Black Horse Prosecution Club” (full name “The Black Horse Prosecution Club for the apprehension and prosecution of felons”) - without Crompton knowing, he might have been quite upset if he had known as he was too proud to be the recipient of charity - bought an annuity for him which provided him with an income of £63 15s per year for the rest of his life. (x200 = £12750 pa as a rough equivalent amount today)

He drew his annuity for about four years until his death 26 June 1827 at the age of 74, leaving the princely sum of £25 and debts of rather more.

RECOGNITION AT LAST

That is not quite the end of the story.

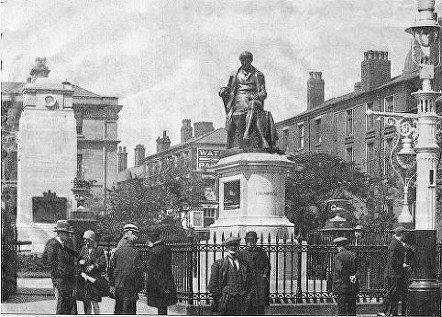

30 years after Samuel Crompton died Gilbert James French a local textile merchant and antiquarian researched Crompton and lectured on him at Bolton Mechanics Institute, persuading the people of Bolton of the significance of Samuel’s contribution to local prosperity and concluding that Crompton had been shamefully neglected by the town. The lecture sparked discussion and debate in the press with proposals including a Crompton literary and scientific institution, the purchase of Hall i’ th' Wood, and the erection of a statue. The institution was favoured but was eventually abandoned and the statue idea revived in 1860. The statue, sculpted by William Calder Marshall was made of electroplated copper by Elkingtons in Birmingham.

The statue. unveiled on Wednesday 24th September, 1862 to commemorate his achievements, was the first civic statue in Bolton. Although only begrudgingly acknowledged in his lifetime, Crompton was finally treated to the recognition he deserved. But even here his bad luck had not gone away. A limestone had been chose for the plinth that could not stand the rigours of Bolton weather and pollution and the statue had to be remounted on the present granite plinth.

Picture posted on Facebook by Denis McCann.

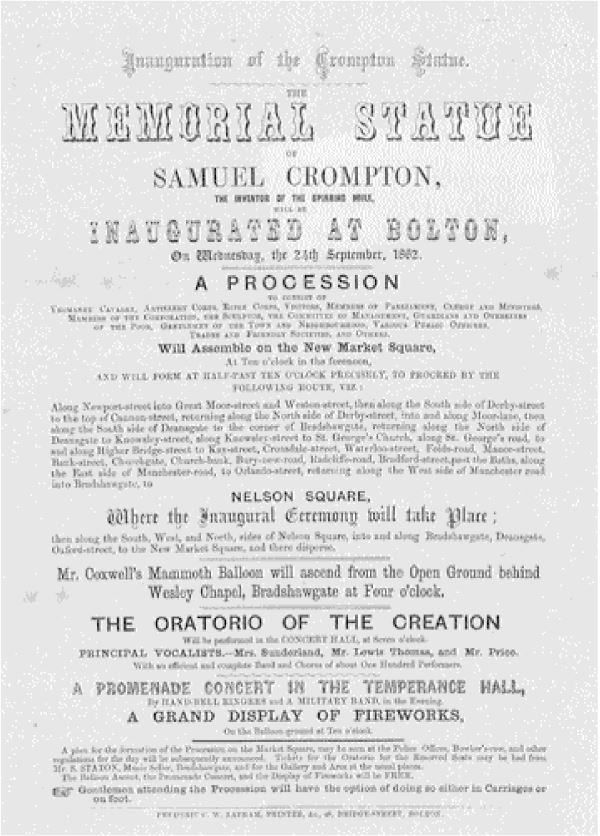

A TRANSCRIPTION OF THE POSTER POSTED ON FACEBOOK BY DENIS MCCANN.

Inauguration of the Crompton Statue

The MEMORIAL STATUE

of Samuel Crompton the inventor of the spinning Mule

Will be inaugurated at Bolton

On Wednesday 24th September 1862

A Procession

To consist of

.............. Members of Parliament, Clergy and Ministers, Members of the Corporation, the Sculptor, the Committee of Maintenance, Guardians and Overseers of the Poor, Gentlemen of the Town and ............ Trades and Friendly Societies and Others.

Will assemble on the New Market Square

At ten o’clock in the forenoon

And will form at half past ten o’clock precisely to proceed by the following route, viz:

Along Newport Street ..... Great Moor Street and Weston Street then along the south side of Derby Street into and along Moor Lane then along the south side of Deansgate to the corner of Bradshawgate returning along the north side of Deansgate to Knowsley Street, along Knowsley Street to Saint George’s Church, along St George’s Road to and along Higher Bridge Street to Kay Street, Crossdale Street, Waterloo Street, Folds Road, Manor Street, Bank Street, Churchgate, Church Bank, Bury New Road, Radcliffe Road, Bradford Street, past the Baths, along the east side of Manchester Road to Orlando Street, returning along the west side of Manchester Road into Bradshawgate,

to Nelson Square

Where the inaugural ceremony will take place:

Then along the south, west and north sides of Nelson Square into and along Bradshawgate, Deansgate Oxford Street to the New market Square and there disperse.

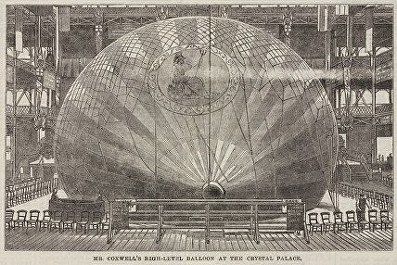

Mr Coxwell’s Mammoth Balloon will ascend from the open ground behind Wesley Chapel, Brashawgate at 4 o’ clock.

The Oratorio of the Creation will be performed in the Concert Hall at seven o’clock

A PROMENADE CONCERT IN THE TEMPERANCE HALL

By handbell ringers and a military band in the Evening

A GRAND DISPLY OF FIREWORKS

Gentlemen attending the procession will have the option of doing so either in Carriages or on foot.

Mr Coxwell's Mammothe High-level Balloon on display at the Crystal Palace.

posted on Facebook by Denis McCann.

In 1952 for the 125th anniversary of his death schoolchildren in Bolton were given a leaflet with some details of Crompton's life and achievements.

Information from:

Bolton MBC information on Hall i’ th’ Wood

www.cottontimes.co.uk of which Doug Peacock is the author and copyright owner (it is no longer on line)

Lancashire Evening Post

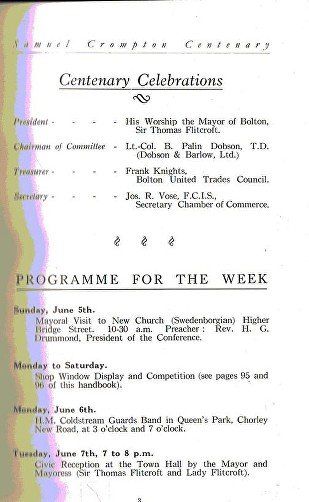

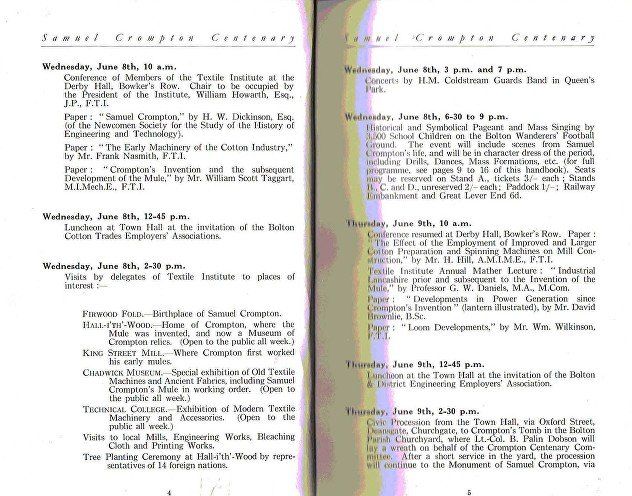

Official Souvenir (of) Samuel Crompton Centenary, Bolton, June 7-10 1927

Denis McCann - the inauguration of the statue

Notes on Swedenborgianism

The New Church (or Swedenborgianism) later “new Jerusalem church”, is the name for several historically related Christian denominations that developed as a new religious movement, informed by the writings of Swedish scientist and theologian Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772). Swedenborg claimed to have received a new revelation from Jesus Christ through continuous heavenly visions which he experienced over a period of at least twenty-five years. In his writings, he predicted that God would replace the traditional Christian Church, establishing a "New Church", which would worship God in one person: Jesus Christ. So it is “Unitarian” but centring on Jesus as God as opposed to God whom Jesus referred to as Father. The New Church doctrine is that each person must actively cooperate in repentance, reformation, and regeneration of one's life. Swedenborg spoke of a "New Church" that would be founded on the theology in his works, but he himself never tried to establish an organization. In 1768, a heresy trial was initiated in Sweden against Swedenborg's writings and two men who promoted these ideas. It essentially concerned whether Swedenborg's theological writings were consistent with the Christian doctrines. A royal ordinance in 1770 declared that Swedenborg's writings were "clearly mistaken" and should not be taught even though his system of theological thought was never examined.[6]

Swedenborg's clerical supporters were ordered to cease using his teachings, and customs officials were directed to impound his books and stop their circulation in any district unless the nearest consistory granted permission. Swedenborg then begged the King for grace and protection in a letter from Amsterdam. A new investigation against Swedenborg stalled and was eventually dropped in 1778.[7]

At the time of Swedenborg's death, few efforts had been made to establish an organized church, but on May 7, 1787, 15 years after Swedenborg's death, the New Church movement was founded in England. It was a country Swedenborg had often visited and where he died. By 1789 a number of Churches had sprung up around England, and in April of that year the first General Conference of the New Church was held in Great Eastcheap, London.

This last paragraph is from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_Church_(Swedenborgian) and is not consistent with another souce.

https://swedenborg.com/.../2015/08/NCE_ScribeofHeaven.pd is a book bublished by the Swedenborgian organisation entitled "Scribe of Heaven". A footnote (23) on page 256 has the following:

in the Lancashire region of England, with a total membership in the hundreds. By 1784,

the Radcliffe society had a Sunday school that accommodated two hundred children, and by

1790, approximately fifty families made up the membership. These groups were run by lay leaders

and were tutored in their understanding of Swedenborgian Christianity by John Clowes (see below);

they sprang up in the villages surrounding Manchester during the takeoff phase of industrialization.

Samuel Compton (1753–1827), inventor of the spinning mule, was the leader of the

Bolton society (founded 1781); James Hargreaves (1720–1778), inventor of the spinning jenny, was a member at Bolton. See Williams-Hogan 1985, 520–550, and generally Dakeyne 1888.

THANK YOU Denis McCann for pointing me to this source.