Samuel Crompton was born in a tiny cottage in Firwood Fold on December 3, 1753, and was only a teenager when he started working on what became the famous Spinning Mule.

But his invention, which streamlined the spinning process, proved to be a pivotal part of the Industrial Revolution and helped make Lancashire a centre of international textile production — thrusting his home town to the forefront of this industry and changing it forever.

For all this, he was never really a success in his own lifetime. He was not a good businessman and was unlucky in a number of ways. But he was a trier, started a number of businesses and cooperated with a number of partners.

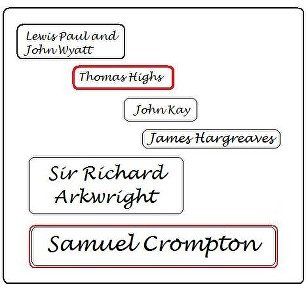

His invention was named “The Mule” because it was thought to be a hybrid of previous ideas, the spinning jenny and the water frame. It produced finer, stronger yarns than its predecessors and was the main stay of cotton thread production in Lancashire for a century and a half. The story of how the parents of the Mule came into being is quite a long and complex one with its share of cheating and dishonesty along the way.

SETTING THE SCENE – TIMELINE 1718 TO 1779

Note for a start that in this story were two men both named John Kay.

Note also the importance of Thomas Highs (Heyes)

1718Thomas Heyes (Highs) born in Leigh

Became a reed maker – essential in looms

A reed kept the warp threads apart and allowed the weft to be packed tight.

Thomas Highs, the real inventor, almost certainly the designer of the Spinning Jenny and the Water frame and possibly having some influence on the design of the Mule as well.

Richard Arkwright was the businessman, the entrepreneur, who got the cotton factory system going, became very rich and was knighted, but....

Samuel Crompton who made the crucial development resulting in the Mule which was the cornerstone of the cotton industry from around 1800 into the 1950s.

John Kay (1) invented the flying shuttle which substantially speeded up weaving and made it that spinners could not produce yarn fast enough. Various people looked for ways to speed up spinning.

Lewis Paul and John Wyatt patented drafting rollers but not very successful. These were sets of rollers through which the cotton slub, that is the very soft and loose pre-spun cotton yarn produced after combing, passed. The rollers worked at different speeds thus drafting or drawing out the slub making it thinner and aligning the fibres. It was tricky to adjust the speed differential to get the required drawing out while not breaking the slub. The tightness with which the rollers gripped the slub had to be precise and constant.

Thomas Heyes (born in Leigh 1719) began trying to improve drafting rollers. He needed help and teamed up with John Kay (2) a Warrington clockmaker. A clock-maker was the right man for the job because he was used to meshing cogs to produce the differing speeds of the minute and hour hands and was skilled at cutting those cogs. Their attempts over many months were not successful and Kay became disillusioned. The story is told that one Sunday evening, they opened the garret window of Highs's house and tossed the machinery out into the street. Kay went home but Highs had second thoughts, gathered up the bits and reassembled them. It seems that he eventually got the drafting rollers to function using a single set of rollers pulling the cotton through a stationary clamp and incorporated this into a working spinning machine that he called the spinning jenny. Jenny after his daughter Jane or as a corruption of “engine”.

Samuel Crompton comes late into the story. He was born 3rd December 1753.

Thomas Heyes produced a spinning machine that he christened the spinning jenny. There is sworn evidence from a man called Thomas Leather whose father was landlord of the Seven Stars in the Walk in Leigh close to where Highs and Kay were working that Highs produced this machine. Highs could not afford to patent his design but made a number of machines which he rented out

The Spinning Jenny had six spindles and so could produce cotton yarn somewhat more than six times as fast as a human spinner with a traditional spinning wheel but could be operated by an unskilled person or even a child. But the yarn produced was too soft for warp and could only be used for weft.

But the story in the history books is that the machine was invented accidentally by James Hargreaves (1764) whose daughter Jenny knocked over a spinning wheel which continued to spin. This gave him the idea of creating a machine working a whole line of spindles from one wheel. History doesn’t tell us how he solved the drafting problem. It may be that James Hargreaves was assisting Highs and took over the spinning jenny while Highs with Kay went back to solving the problem of drafting rollers. It seems likely that Hargreaves did make a number of improvements to the spinning jenny. Was the Spinning Jenny named after Hargreaves' daughter (so folk lore says) or was it, jinny or jenny, just a Lancashire form of the word "engine" (more likely)?

In 1766 Hargreaves built his own machine with eight spindles instead of six and produced machines for friends and family to use. Robert Peel, the grandfather of the so-named Prime Minister, installed some in his Brookside mill. In fact it is thought that Peel may have had considerable input into the development of the spinning jenny. But neighbours were jealous of Hargreaves ability to produce more yarn than they could.

In 1768 an irate mob gathered at Blackburn's market cross and marched to Stanhill, where they smashed the frames of 20 machines he was building for Peel in a barn. (Samuel Crompton also had problems with machine-breakers and a Luddite riot in Westhoughton burned down a mill, Westhoughton Mill or Rowe and Dunscough's Mill, in Mill Street on 24 April 1812, forty years after the machine breakers destroying Hargreaves and Peel’s machines. On this occasion nine men were deported and four hanged.)

1770 - Hargreaves finally took out a patent on the spinning jenny but it was too late because hundreds of copies had already been made and improvements were seeing machines with up to eighty spindles.

1760-1767 Meanwhile, Kay and Highs finally produced a design for the drafting rollers where the second set of rollers rotated at exactly five times the first set so stretching the slub (roving) to five times its original length prior to being given its twist. This new machine required more effort than a person could sustain so almost from its earliest days it needed a source of power – in the 1760s the only such power was the water wheel and the device became known as the water frame for that reason, not because water took any part in the spinning process, although one attempt was made to produce power by horses. The water frame finally could produce harder and stronger thread than the previous mechanical devices – which could be used for warp as well as weft.

Highs gave Kay a wooden model of what was to become the water frame and asked Kay to make it in metal which Kay did before returning to live in Warrington.

Now we need to step back in time a little.

In 1732 Richard Arkwright was born in Preston.

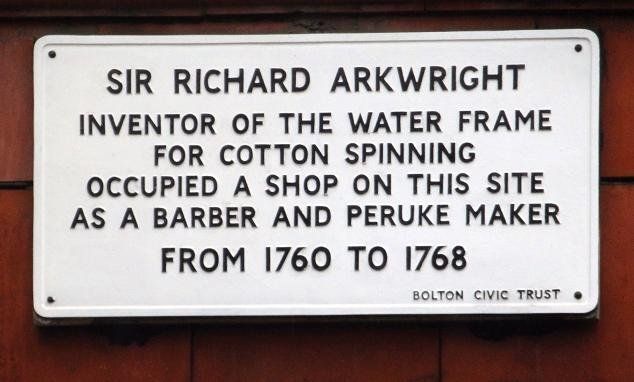

In 1755 he opened a barber’s shop on Churchgate in Bolton. He was an entrepreneur from a young age. He bought and ran the Black Boy pub and became an expert wig, or peruke, maker alongside his haircutting. He travelled widely to buy hair for his wigs. During these travels he heard of the efforts to speed up the spinning process and met both Thomas Highs and John Kay.

In 1767 Arkwright, on his business travels, met Kay. gained his confidence, and over a drink in a pub persuaded him to hand over the secrets of Highs' machine. With Kay in tow - presumably to prevent him from talking - he decamped swiftly to Preston, bought the clockmaker's loyalty with the promise of a job, and found an investor willing to back development of the water frame. Highs might not have patented his invention because of lack of money but Arkwright had no such problem. In 1768 he moved to Nottingham and a year after that patented the water frame as his own invention.

The Villain of the Piece !---->>

In 1771 Arkwright built a large factory on the banks of the River Derwent in Cromford near Matlock Bath, Derbyshire and filled it with water-frame spinning machines.

Although there had been a large silk factory in Macclesfield almost fifty years earlier, the Cromford Mill is regarded as the birth of the cotton factory system.

Arkwright became a very rich man and was knighted. He was a skilled entrepreneur, he seized opportunities and got things done. He is regarded as the founder of the cotton industry.

In 1774 Arkwright persuaded parliament to remove the crippling cotton tax – which made him even richer but also helped everyone in the cotton industry.

His company later had a presence at Sunnyside Mills.

Part of Sunnyside Mills, Daubhill, Bolton

The notice says, "Sir Richard Arkwright Co.

English Sewing Ltd."

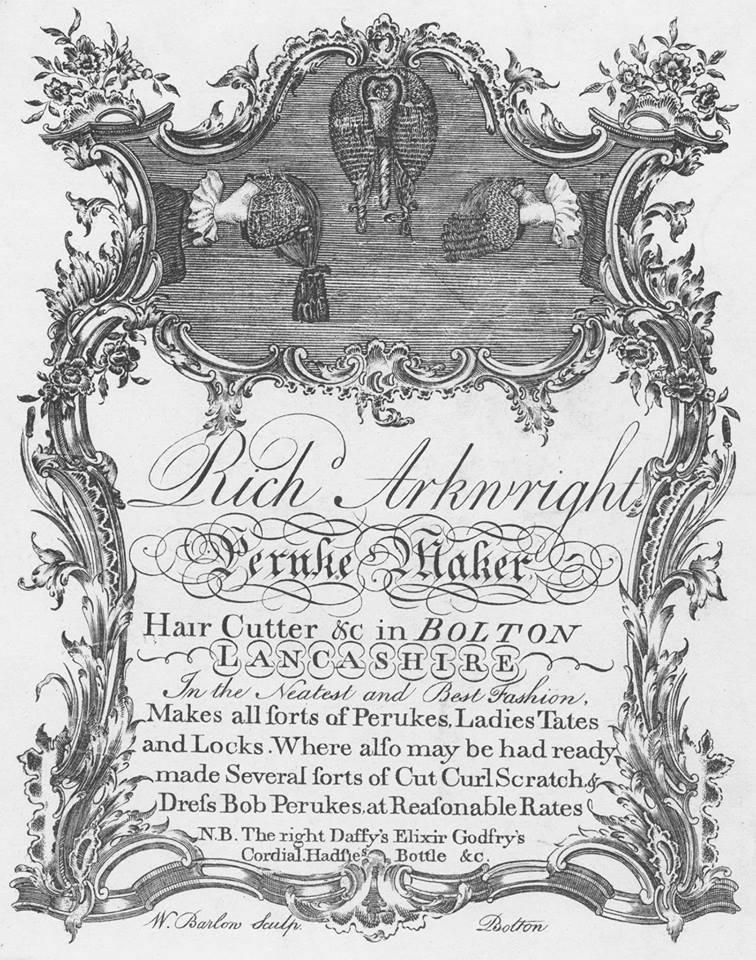

A flyer which advertised Richard Arkwright, Hair Cutter and Peruke Maker. A peruke was of course a wig. Note the use of the "long s" which looks like a "f" but with the cross bar pointing backwards instead of forwards. So not "all forts" but "all sorts". >>>>>>>>>>

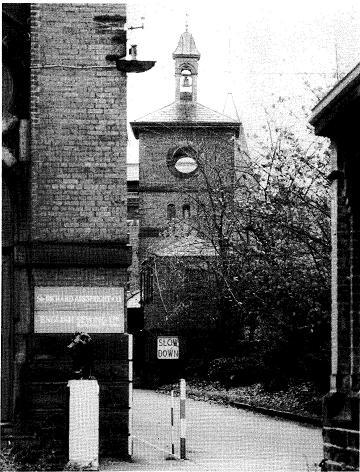

The area of Churchgate, Bolton where Richard Arkwright had a barber's shop. Note the white plaque on the newsagent's shop, between the Brass Cat and Booth's music shop.

The plaque. Whether it is true that he was the "inventor" is a moot point. The text shows that he probably wasn't.

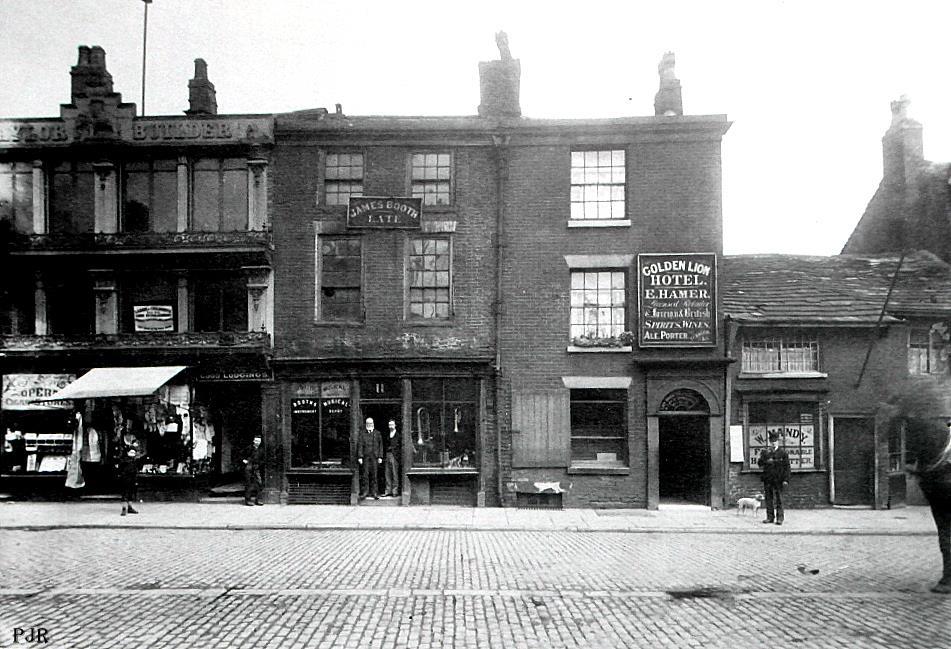

The same area of Churchgate around 1900 but the buildings may be the same as they were around 1755.

Note James booth's with the brass instruments in the window. Booths was to the left of the Golden Lion until it moved in the 1960s. Then we have the Golden Lion which became known as the Brass Cat (unofficially at first) in the 1960s.

Then we have W Mandy's shop which is where Arkwright had had his barbers

1775 Arkwright developed cotton spinning into a continuous process, patenting a variety of machinery that performed all the processes of manufacture, from cleaning to carding to final spinning. But some writers say that not one of the ideas parented really belonged to him.

In 1781 he went to court to protect his patents against people copying his machines but instead his patents were overturned. In further court cases his patents were restored but later the truth came out and all his patents were permanently set aside. Highs, Kay, Kay's wife and the widow of James Hargreaves all testified that Arkwright had stolen their inventions.

1772 Crompton began work on the Mule.

1779 Crompton produces the Mule.

On the next page we look at Samuel Crompton himself.